Making Meaning: Jared Frank on Design, Purpose, and the Path Ahead

For my very first interview, I had the pleasure of sitting down with my dear friend Jared Frank and photographing him at his Silverlake home, Casa Larissa, which he shares with his wife, Krista Mileva-Frank. Jared is an extraordinary interior designer based in Los Angeles, whose work has been featured in Architectural Digest, Dwell, LA Times, Apartment Therapy, Domino, and more. Krista, a rising art curator and design historian pursuing her PhD at MIT, truly deserves an interview of her own.

I first met Jared years ago at one of the unforgettable gatherings he hosted at Casa Larissa. Even then, it was clear he was a magnetic force within a vibrant, eclectic community—effortlessly bringing together diverse voices, perspectives, and creative energies. Under his roof, music, theater, conversation, and artistry naturally collided, creating an atmosphere where ideas and inspiration flourished. Whether through his design work—which consistently reflects soul, intention, and originality—or his innate gift for uniting wildly creative and diverse personalities, Jared possesses a rare ability to cultivate both beauty and belonging.

In our conversation, Jared opened up about the roots of his perspective, the creative process that shapes his projects, and the partnership with Krista that continues to inspire his path forward.

When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grow up? Were you always a curious kid?

I’ve always been extremely curious, and I think curiosity might really be the starting point for all of us. Even before thinking about careers, I was completely obsessed with blocks and building things, or making forts out of cardboard boxes—you know, the classic joke about kids preferring the box to the present. I loved wandering in the woods, marking spaces with string and collecting interesting objects. Trips to the beach meant gathering shells and stones and organizing them meticulously.

Looking back, it’s easy to see a pattern that could point toward becoming an architect, a designer, or a collector. There were other things I loved doing as a kid too—things that if I had ended up in a different occupation, I could reverse-engineer as signs. I loved storytelling—spending hours with my stuffed animals, inventing elaborate backstories and narratives for them. As an only child, I also learned to spend a lot of time alone and entertain myself.

Jared and Krista at their Los Angeles home Casa Larissa

Do you remember what first sparked your interest, particularly in design. And was there a moment or a space that lit that spark?

For me, the first thing that sparked an interest in space during my teenage and early twenties was actually how much I didn’t like most spaces and how uncomfortable most of them made me feel - whether that was because of the lighting, what was allowed in them, or their corporate or claustrophobic qualities. I was generally less impressed by space than most people, and that discontent made me want to change it.

As a young teenager, that meant decorating my first bedroom, expressing my identity across every surface. Later, when I got my first car at 16, I decorated the interior with Christmas lights, funny upholstery elements, and holiday décor.

“The first thing that sparked an interest in space during my teenage and early twenties was actually how much I didn’t like most spaces and how uncomfortable most of them made me feel - whether that was because of the lighting, what was allowed in them, or their corporate or claustrophobic qualities. I was generally less impressed by space than most people, and that discontent made me want to change it.”

But even earlier than that, I remember being extremely impressed by the atrium vestibules in John Portman’s architecture. In Los Angeles, he designed the Bonaventure Hotel, which has this enormous glass atrium. You enter the space, then step into an elevator that moves along the inside and outside of the building, bursting through the atrium and climbing the exterior.

The first time I spoke more than a word was at John Portman’s Marriott in New York City. It’s an incredible atrium where the floors shift above an open courtyard, repeating in grand, geometric patterns. At the very top of the glass atrium was a single red dot. I yanked on my mom’s hand and said, ‘Look, Mom, balloon.’ That was the first full sentence I remember saying. Even years later, I was still amazed by those spaces and their repeated architectural grandeur.

A rubber prototype of Jared’s latest lighting fixture design.

You studied film at some point, and then your interest in film and art took a pivoting point. Can you tell more about that?

I’ll back up a bit, because I’ve really had three careers in my life. I started dancing at the age of nine, and from nine to eighteen, I devoted all my time outside of school to dance. Then, in undergrad, I devoted myself for a similar period to film—from about eighteen to twenty-seven or twenty-eight. At twenty-seven, I had another career shift and started designing.

These phases aren’t completely separate—they flow into one another, overlapping and influencing each other, with clear demarcation points along the way.

“When I moved to Los Angeles, I had a brief period where I wanted to reconnect with the creative scene, so I started production designing to get on set and meet people. I even redressed a location for a music video—so thoroughly that the homeowner came home to find I’d redecorated his home. He ended up hiring me to decorate other spaces.”

In high school, I began making dance films—filming, editing, and sometimes experimenting with non-dance subjects. For example, I once filmed Styrofoam being thrown down a stairwell and edited it to create a narrative rhythm based on how it bounced and broke. Having danced tap for years, it felt like tap dancing with video.

The film I submitted to NYU for undergrad was shot during a seven-hour bus ride from summer camp to New York City, where I performed dance. I filmed all these things out the window and then edited them into a rhythm, similar to a Michel Gondry music video. At NYU, I initially focused on experimental film—‘what if dance was a movie’ kind of films—but over time, I evolved toward narrative work, always keeping rhythm and style at the core.

When I moved to Los Angeles, I had a brief period where I wanted to reconnect with the creative scene, so I started production designing to get on set and meet people. I even redressed a location for a music video—so thoroughly that the homeowner came home to find I’d redecorated his home. He ended up hiring me to decorate other spaces.

From there, I transitioned into light renovation, which led to interior design. My first true interior design project was Tenants of the Trees, a giant warehouse space where I removed walls and parts of the ceiling, then built out an entire interior space with multiple rooms. That’s when I started dealing with interior architecture.

As my interior design work grew, I expanded into furniture and product design, creating custom art furniture for specific projects. Today, I also design independent furniture lines that aren’t tied to any client project.

So, that’s been my path—from dance, to film, to design—each phase informing the next and shaping the way I approach creativity.

What does your creative process look like, where do your ideas tend to begin?

One thing I think a lot about in interior design is how architecture and interiors enable—or limit—certain behaviors. When you design a space, you’re essentially designing what can happen and where.

Wildcrust LA, a Highland Park restaurant in Los Angeles, designed by Jared Frank Studio - Photographed by Tim Hirschmann

“The goal is to create a diversity of options, so people can find where they want to be. Even more, you want to design a narrative—so moving from one experience to another feels natural”

Take Tenants of the Trees, for example—a bar, nightclub, and café. You have to consider multiple scenarios: you start to think about: Okay, I’m on a date with someone, and I want an intimate place to curl up and hear each other. Or I’m in a large group, and I want to start by hanging out with them, but eventually end up on the dance floor and maybe meet someone there. Or maybe I just want to go out. There are countless reasons people visit a nightlife venue, and so many different personalities to account for. The question becomes: Where in this varied space do all those things happen?

Tenants of the Trees, a night club, café, and bar in Los Angeles, designed by Jared Frank - Photographed by Ryan Schude

Tenants of the Trees - Photographed by Ryan Schude

The goal is to create a diversity of options, so people can find where they want to be. Even more, you want to design a narrative—so moving from one experience to another feels natural. A common mistake is simply labeling rooms: ‘Here’s the dance floor, here’s the bar,’ without considering the flow. Thoughtful design considers adjacencies, surprises, and signals about what behaviors are acceptable. Spaces can encourage formality, or they can invite people to get up, stand on banquettes, and dance.

“ Thoughtful design considers adjacencies, surprises, and signals about what behaviors are acceptable.”

Apartment in Cambridge designed by Jared Frank - Photographed by Jared Kuzia

A bedroom in Cambridge apartment - Photographed by Jared Kuzia

I approach homes the same way. A client might say, ‘In this room, I want to work, eat, and entertain.’ Often, I push back: you don’t need to do everything everywhere. Each activity deserves a dedicated space, designed to maximize the experience.

Ultimately, I see spaces as humanistic: focused on what humans can do and how they interact with their environment. When I transform a home into a concert venue, for instance, I start by asking not what looks good, but what will allow people to experience a specific outcome—a narrative within the space.

This philosophy even ties back to film and production design: those are also spaces where stories are told.

Jared with his “Fertility Table” design.

You design far beyond interiors—you create furniture, objects, and, really, experiences. When you're working on something tactile, like a custom object or a piece of furniture, where does the vision begin? What tends to spark or shape the idea?

I rarely start with the tactility of materials. Usually, I begin in SketchUp, a free 3D CAD program anyone can learn. In SketchUp, everything is just white lines forming boxes, cylinders, and spheres.

For furniture, I often draw the entire piece this way. Take the table line I’m working on now—it started completely abstract. At that stage, I had no idea what the actual materials would be. Later, it became clear: these planes would be glass tables. Then came the question: what about the pebbles that support and pass through them? I drew these shapes and variations , and considered materials for both price and look.

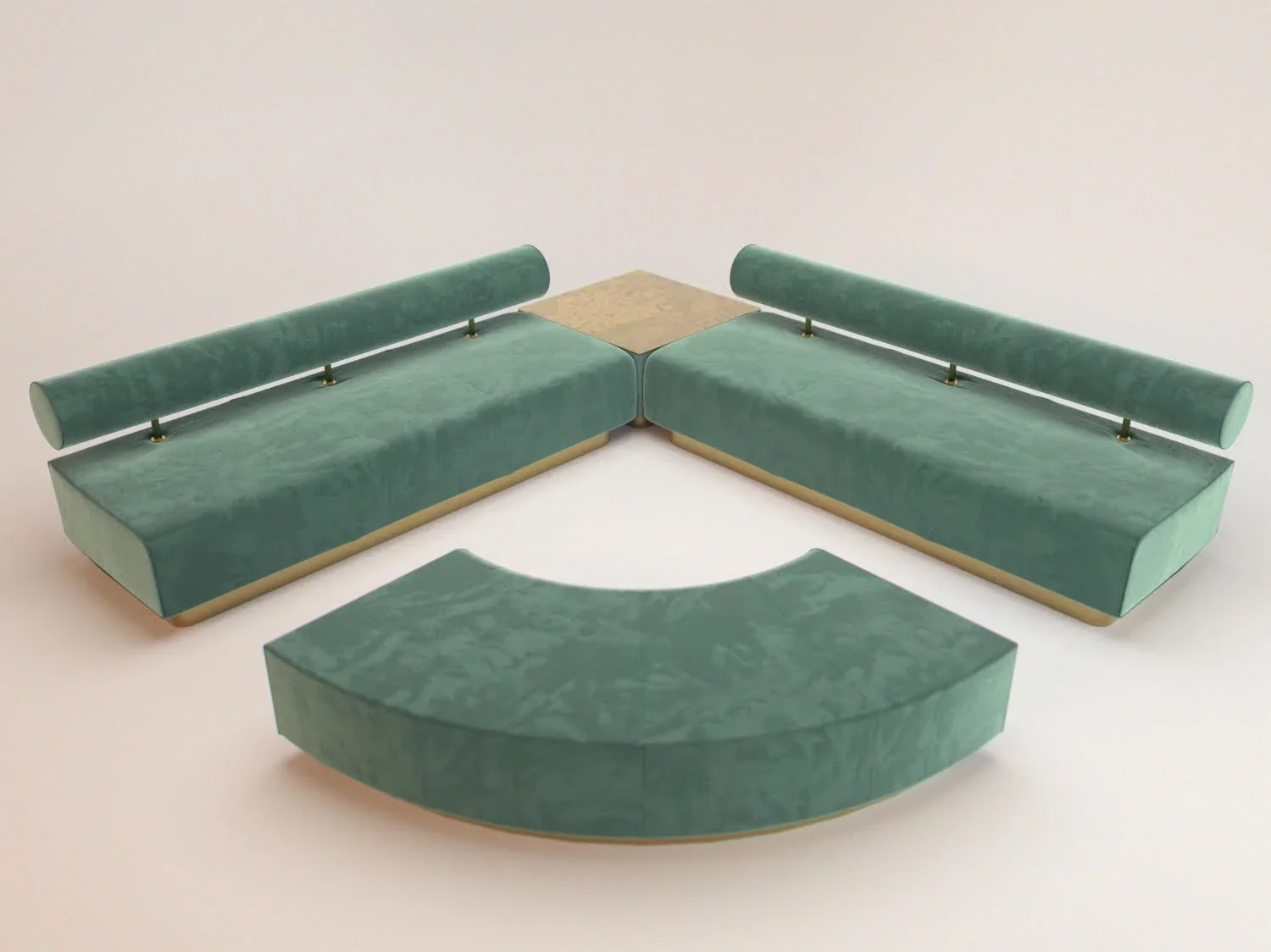

Hammerhead - A bespoke made-to-order sofa by Jared Frank Studio

We’ve been in a long prototyping phase. At one point, we decided to pour the pieces rather than carve or turn them—concrete, polished but also rough, experimenting with colors. Once the system was assembled, we explored other possibilities. We looked at the rubber molds for the concrete, we thought: wouldn’t great to reverse and make these pieces out of rubber?

Rubber behaves differently than concrete—it has a different price point and properties. Light can pass through it, which opened the door to thinking of these shapes as potential lighting pieces.

“For me, design is a process of discovery rather than starting with a fixed end in mind. You don’t necessarily know where you’ll end up when you start. And I think that’s where the creativity lives—in that unfolding.”

I’m not a craftsperson. Some designers begin by becoming incredible woodworkers or ceramicists, letting the material dictate the form. I start with shape and space, then determine which vendors can realize the vision—cutting aluminum, pouring concrete—in order to create the pieces I’m designing.

For me, design is a process of discovery rather than starting with a fixed end in mind. You don’t necessarily know where you’ll end up when you start. And I think that’s where the creativity lives—in that unfolding.

Anyone who knows you and has spent time in your home knows it feels like an extension of you—soulful, textured, full of stories. It's like a living cabinet of curiosities, rich with patina and personality. There's a deep sense of history in your design choices, as if each object was chosen not for how it looks, but for the life it has lived.

I actually remember you telling me a story behind the taxidermied bugs on your wall—although they’re not there anymore. Where does that sensibility come from? Have you always been drawn to things with a past and with character?

First off, this house has a past and a character. It’s interesting that so many people associate it with me, because most of my work is very much authored by me. But this house is a collaboration—a collaboration with history and with the previous tenant. Lance Clem, the fresco artist, created all the murals, and I’ve moved into his art piece. My job has been to decorate around his trompe l’oeil frescoes. Even though we didn’t work together directly, I inherited something and now express my life within his space which is actually kind of similar to the way I work with a lot of clients.

“You can see history in an object. The most obvious indicators are its wear or patina, but often it’s the stories we tell about it—or even when a story remains mysterious, the sense that there is a story behind it.”

When they bring me an architecturally significant home, often we are not creating an original piece in a white cube room. We're working with some significant space that was either designed by a previous architect or designed through a history of interventions. The challenge is translating that history into the present moment and into the life of the person living there.Ultimately, the home becomes a portrait of its current occupant—but that portrait is never separate from history.

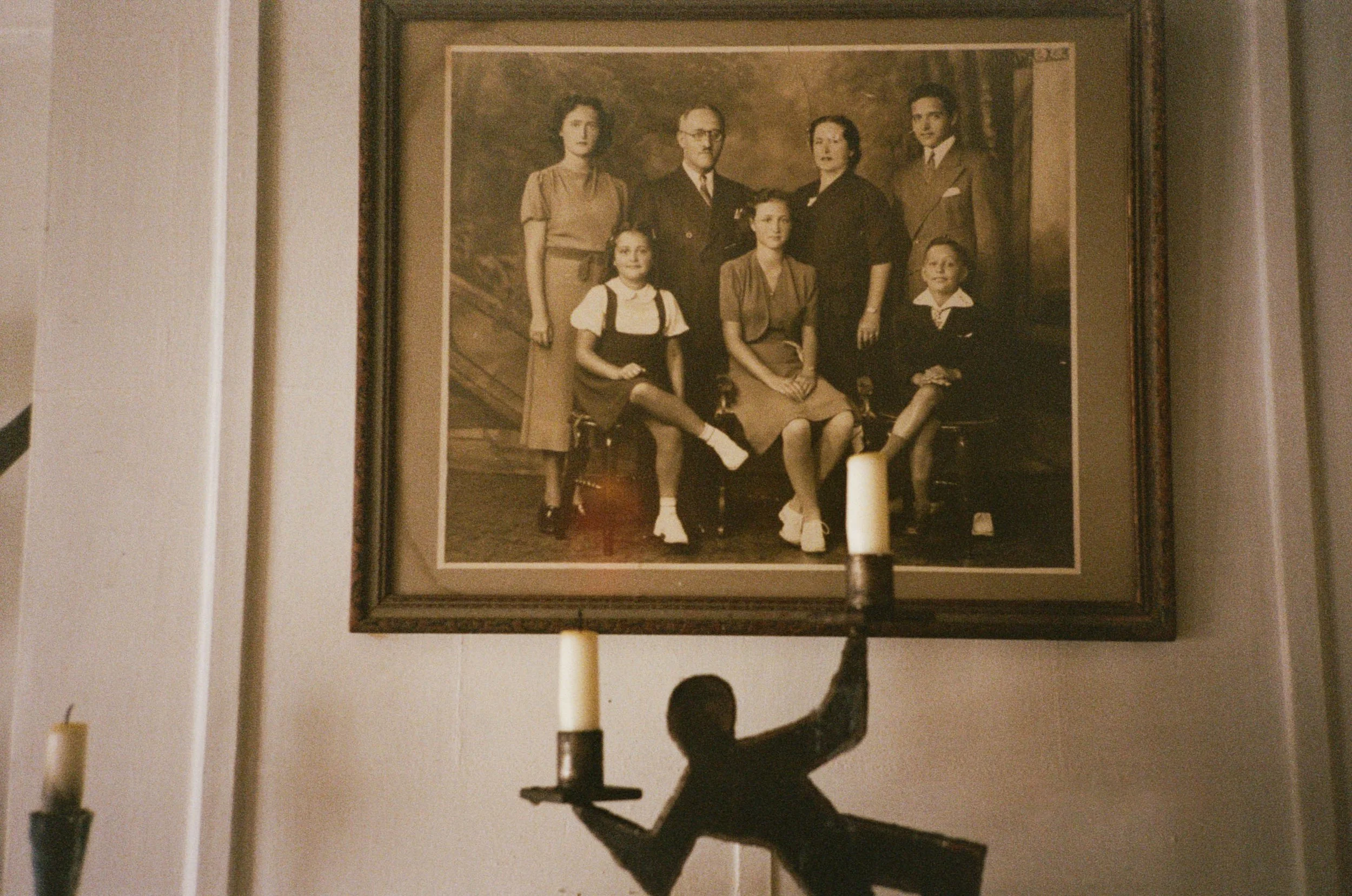

A Frank family portrait hangs above Jared Frank’s mantel.

I think the same can be said for objects. You can see history in an object. The most obvious indicators are its wear or patina, but often it’s the stories we tell about it—or even when a story remains mysterious, the sense that there is a story behind it.

In my home and antique collection, I really like to collect anonymous items. Sure, you can point to an Eames chair—and Eames chairs are great—but it feels like it just is. It exists right now. A one-of-a-kind object without a known designer invites imagination: maybe you notice a faint maker’s mark, suggesting someone just learning to weld, or perhaps it was an illustrator experimenting with woodworking because it’s so well drawn but not as well built. It's interesting to imagine and think about the past history to objects.

This home, in particular, has a cabinet-of-curiosities quality. That sensibility traces back to my mother, who wrote extensively about wunderkammers, the German term for “cabinet of curiosities.” The earliest museums were exactly that: collections where fine art sat alongside historical artifacts, anthropological finds, and even fakes. My home isn’t a scholarly museum—it’s a collection designed to spark wonder and questions.

I love that guests often ask about the objects they encounter—like you did about the bugs, which aren’t there anymore. The home does change, but some of the things in the home are just designed to provoke both your wonder, but also then your dialog with me as a guest.

Are there any daily rituals or habits that help keep you grounded or inspired?

I actually find mornings a little hard. I probably wake up a bit too early and drink a bit too much coffee. I’m sure there’s a better version of my mornings—one where I stretch and drink green tea. Maybe that’s what the next ten years will bring: a transition into better mornings.

But often, what I do is just get out of the house.

We’ve talked about my home being a theatrical space—and it really is. It can feel overwhelming, full of stimuli. Early on, I realized it’s crucial for me to leave and go somewhere with fewer distractions, where the only thing to do is work. That might be client-directed work, or—if I have a rare window without deadlines—I’ll ask myself, Okay, what am I making?

“There’s a reason I love working in pre-existing buildings. Contraints fuel my creativity. It’s why I’ve never been comfortable thinking of myself as a fine artist. Creating something that could be anything for a white-box gallery space actually paralyzes me .”

In fact, the furniture I’ve designed and the product lines I’ve developed all came out of those periods of open time. When a client says, “Great, give me four days and I’ll get back to you,” I still show up at the office—but I have to invent work for myself. Being in a space where there’s nothing else to do—no dishes, no bed, no family calls—is incredibly helpful for creativity.

Limits have also been essential to my process. There’s a reason I make tables instead of sculptures: they must meet specific height, width, and depth requirements. There’s a reason I love working in pre-existing buildings. If someone says, You can do anything you want, but it’s a Spanish-style building from 1929, you quickly realize you can’t do anything you want—you have to consider how the present interacts with the past.

Those constraints fuel my creativity. It’s why I’ve never been comfortable thinking of myself as a fine artist. Creating something that could be anything for a white-box gallery space actually paralyzes me. Constraints work better. Even in film—if someone says, Make a noir with a comedic lead, suddenly you have a spark. But if someone just says, Make a movie, the sheer number of possibilities can be overwhelming.

As we speak, I can see that you truly love your work and it really excites you, which is a wonderful thing. Is there a particular project you’ve been working on lately that you feel drawn to share?

Well, I’ll tell you about the two things I have going on right now.

One of my favorite restaurants in Los Angeles, Genghis Cohen, has been around for 40 years. It emerged from a rock-and-roll milieu—a Jewish New Yorker came to L.A. with nostalgia for the American-Chinese food of his youth, and he created an entire music scene around it. It is like a small concert venue along with a restaurant. Over time, it has become an American Chinese rock and roll space that's part of LA's ferment in history.

Now, they’re being forced to move by their landlord, and I’m working with them on a temporary pop-up space. For me, the excitement there is to begin experimenting and collaborating with the client—but the ultimate goal is designing their new permanent home and to imagine maybe it’ll exist for another 40 years.

On the self-directed side, most of my earlier furniture pieces were either licensed—designed in Italy and manufactured for sale—or commissioned for specific projects, like sconces made for a particular restaurant.

Genghis Cohen in Los Angeles designed by Jared Frank - Photographed by Lucky Tennyson

Now, for the first time, I’m developing a couple of furniture lines entirely on my own. They’re not tied to a client or a project; they’re simply pieces I want to make. We’re figuring out how to manufacture them here in Los Angeles, which has been really exciting.

It’s a bit of a risk because, for the first time, I’m investing my own money. I’m used to working with clients’ budgets. And while client work can be inspiring, the reality is that most clients, like in any field, tend to make the project more complicated. Sometimes it’s economic constraints, but often it’s just a matter of closed-mindedness.

Navigating that dynamic—helping clients articulate what they want and understand what’s possible—can elevate a project, but it takes as much effort as the designing itself.

When you’re working for yourself, there’s none of that negotiation or compromise. You can simply ask: What do I think is best? And that freedom is incredibly refreshing.

What does a fulfilled life mean to you—and has that meaning evolved over time?

A fulfilled life definitely involves community—and family.

I love my work, but even that is about impact: how the things I create affect people, how the things I make impact people and how the life I live impact those around me?

At this point, with the incredible partner I have—Krista—so much of my sense of future and possibility revolves around what we can build together. That includes being together, but also navigating the challenges of our dual careers, which often keep us apart.

“I love my work, but even that is about impact: how the things I create affect people, how the things I make impact people and how the life I live impact those around me? “

My idea of family encompasses the biological family that hopefully Krista and I will make with a child if we are able to soon—but it also extends to my friends and community. Happiness, for me, involves still hanging out with old friends from high school, college, and my career, while remaining open to new friendships and experiences. It’s about staying present while holding a vision for the future.

Those goals, much like in the furniture-making process, are nebulously defined. That way, the joy is in the steps along the way. Anyone who has ever pursued a goal they believed would bring happiness and achieved it eventually realizes that a sense of dissatisfaction remains. True fulfillment comes not from reaching the goal, but from enjoying the process of working toward it—setting new goals, shifting priorities, and expanding ambitions. It is in the journey, not the destination, that we find joy in life.

Looking ahead, what do you hope to explore or become? What do you want to be when you grow up?

Maybe it’s the same answer for all of these questions.

When I was a kid, I barged into my parents’ room and said, ‘Mom, Dad, I just watched the greatest movie. You have to see it!’

They asked, ‘What movie is it?’

And I said, ‘It’s *To Kill a Mockingbird!’

They were like, ‘Ohhh…’

And I said, ‘Yeah, I love it. Look at this guy!’—pointing at Gregory Peck. ‘Mom, Dad, I want to be him when I grow up.’

Of course, they assumed I meant a lawyer—the classic parental dream. But I said, ‘No, I want to be a dad.’

So, you asked about my current goals. I’ve been talking around them—mentioning Krista, our hopes for a family—but yes, I do hope, without jinxing it, that becoming a father will open the next stage of my life.

And naturally, I imagine it will also spark a new stage of creative work. I’m sure I’ll start thinking about designing things for children.

Discover more of Jared Frank’s design philosophy and recent projects at https://jaredfrank.studio.

Photography, Words & Interview by Basak Barrett

Additional Photography by Ryan Schude, Jared Kuzia, Tim Hirschmann & Lucky Tennyson